Barcelona, Spain. 28th October 2018.

(Bottom of page for Recent Posts, Top Posts, Subscribe and Search. Clicking image doubles size. Trip summary and links to posts.)

.

First we stopped by at Fundació Joan Miró.

.

Lovers playing with almond blossom (1975).

Model for monumental sculpture installed at La Défence, Paris.

.

.

.

The diamond smiles at twilight (1947).

.

.

.

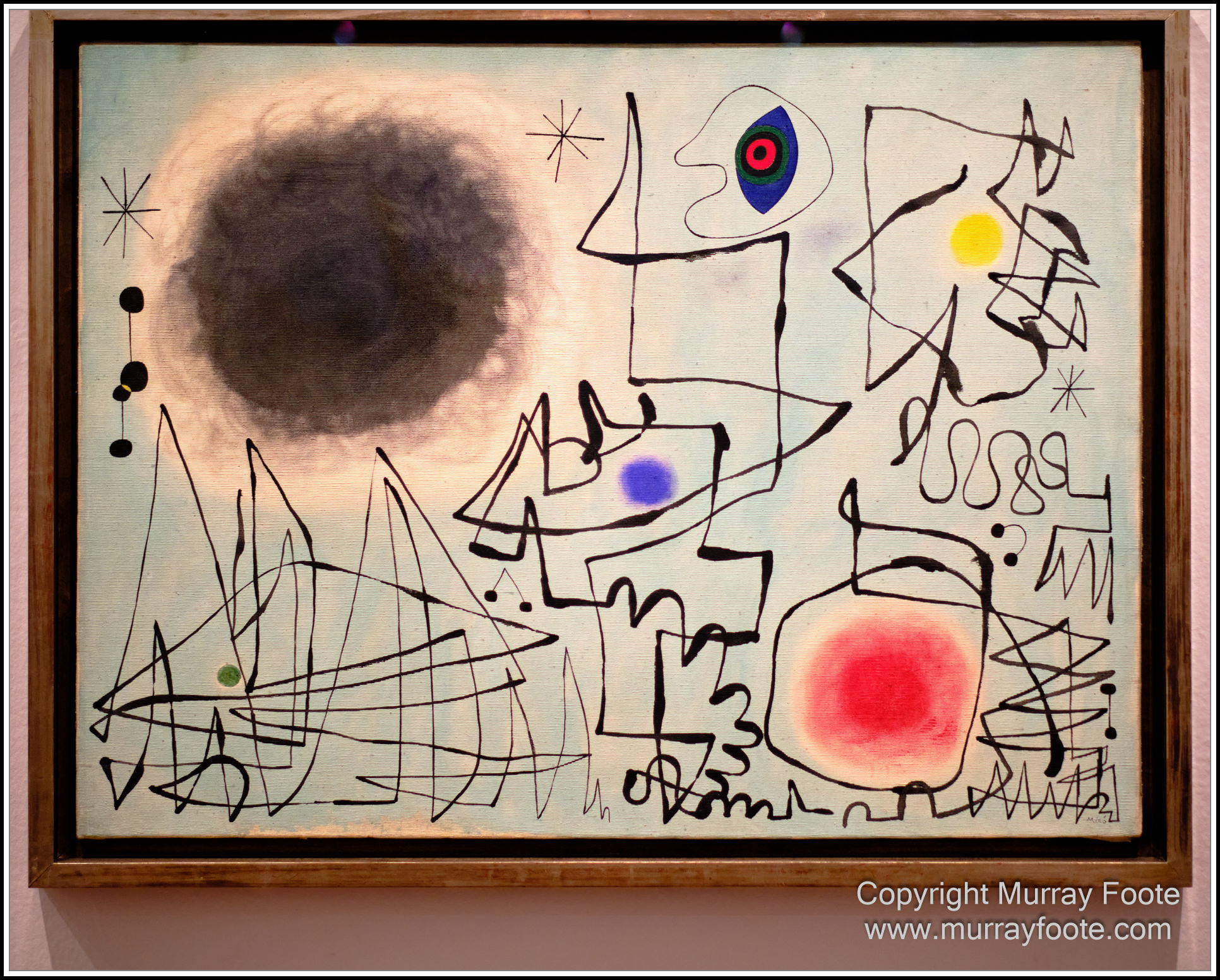

The morning star (1946).

.

.

.

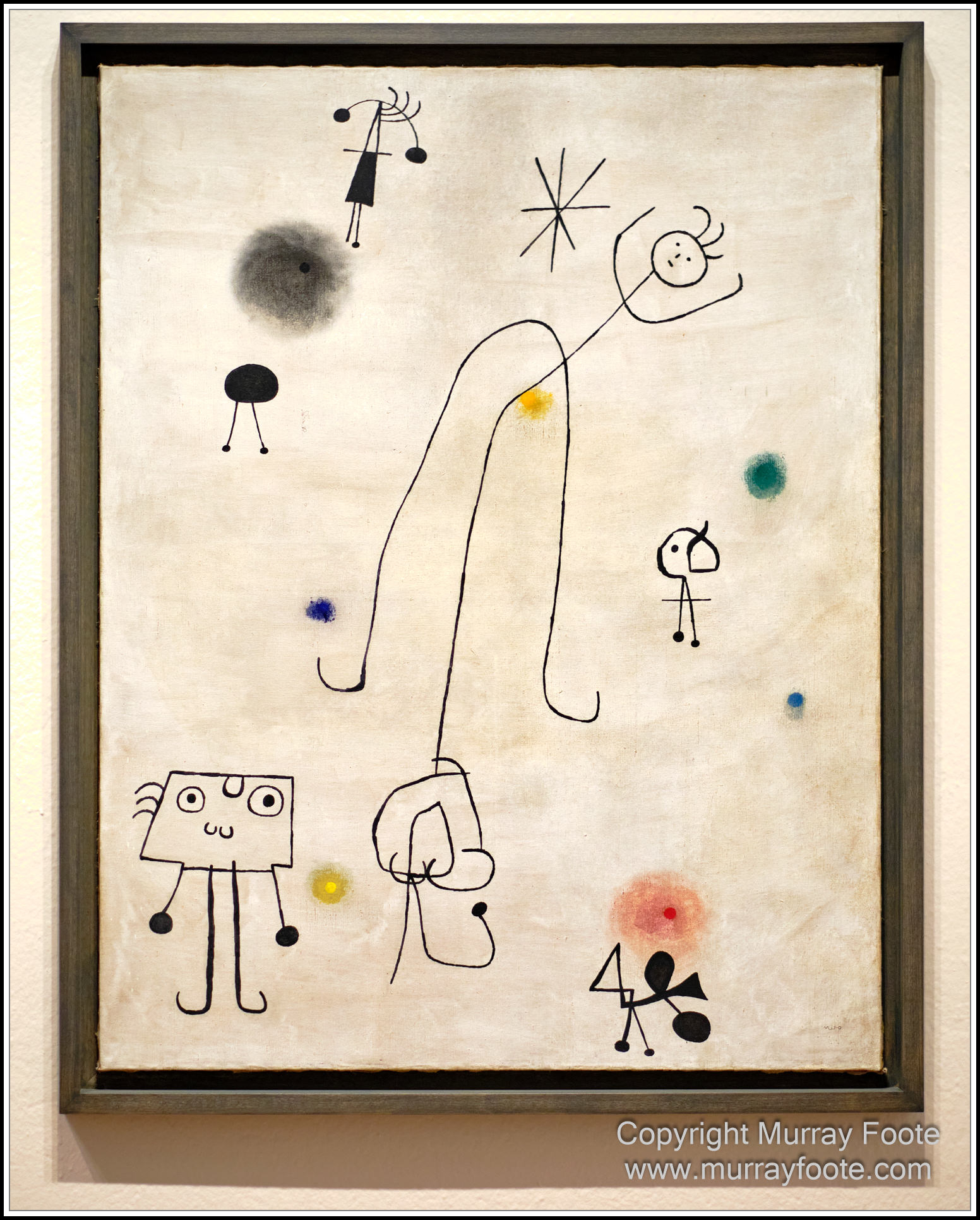

Woman dreaming of escape (1945).

.

.

.

No description for this one.

.

.

.

.

Tapestry of the Fundamentació, 1979.

.

.

.

After Miró, we teleported up the hill to the Castel de Monjuic.

In 415, the Visigoths became administrators of Barcino (which gradually became Barchinona) and they remained after the fall of the Roman Empire until the arrival of the Moslems.

.

.

.

The castel itself is more sparse than many historical sights and the interest is as much the views you can see from up there. Here are a couple of the port area..

Unlike further south, Barcelona did not have a long period of Moorish rule. They took it over from the Visigoths in 716 but Louis the Pius, son of Charlemagne, moved in in 801 after a siege of several months. Coming along the coast to Barcelona did not require crossing the Pyrenees. It was then ruled for several centuries by Caroligian (French or Frankish) counts. They were initially appointed by the Carolingian Court but after Wilfred the Hairy in 878, became hereditary. Catalonia was gradually united under the Counts of Barcelona and it remains a distinct cultural and linguistic entity.

.

.

.

Port area (bird’s eye view). There may have been some changes in the last thousand years.

The County of Barcelona united in marriage with the Kingdom of Aragon in 1137 but they remained separate political identities. The navy of Barcelona also come to develop an overseas maritime empire for Aragon including including Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Sicily, Naples, and Athens. The last Count of Barcelona died in 1410 and Aragon was weakened by a civil war from 1462 to 1472. This was unusual for the times in that it was fought not merely between claimants for thrones, but to defend the laws and constitutional rights of Barcelona’s citizens. The marriage of Ferdinand II of Castile and Isabella I of Aragon in 1469 led to a single Spanish monarchy based in Madrid, and discoveries in the New World reduced the relative significance of the Mediterranean. Power gradually shifted from Aragon to Castile.

.

.

View from the castle walls.

There was a beacon on the top of the hill at least as early as 1073. In 1640, at the beginning of the Revolt of Catalonia (1640-1652) the citizens of Barcelona built a fort here to counter the threat of a naval siege by Philip IV. There was briefly a Republic of Barcelona but following defeat at the Battle of Martorell, they opted to accept the French as overlords, which redoubled the efforts of Spain to suppress the revolt.

.

.

.

Passageway to the main courtyard.

In 1641 the Spanish attempted to take the fort and the hill from the citizens of Barcelona but were beaten back in the Battle of Montjuic. The Spanish were able to recapture Barcelona in 1652, after a year of siege. There were further improvements to the castle at the end of the seventeenth century when the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697) resulted in a series of maritime attacks and sieges.

.

.

.

Coat of arms of Charles II, whose death gave rise to the War of the Spanish Succession.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) came about after Charles II, last Hapsburg ruler of Spain, died childless. His nominated successor was Phillip of Bourbon, Duke of Anjou, who became Philip V, king of Spain. This was contested by Hapsburg Archduke Charles of Austria, who was also proclaimed king as Charles III. Catalonia entered this was in 1705 on the side of Austria. Bourbon troops tried to take the castle and the city in 1706 but were beaten back. War continued until a successful siege by Bourbon troops in 1714. The castle was largely destroyed by then and a new castle was quickly developed, with work starting in 1753 and finishing in 1779.

.

.

.

The main courtyard, capable of holding a large number of troops.

In the md-19th century there was conflict between liberals and conservatives and three Carlist civil wars. The Carlists opposed a female succeeding to the throne. (They also later supported Franco in the 1930s but were then dismantled by him rather than creating a Carlist monarchy.) Barcelona was often in effective rebellion during these times for differing reasons. There was free trade impacting on an organised textile industry, unpopular taxation, support of the Carlists, and revolutionary demands for distribution of wealth. General and politician Espartero three times shelled the city from the castle, in 1842, 1843 and 1856, with considerable loss of life and damage. In 1843 there were 350 deaths, 434 injuries and 40,000 fled the city. The castle was also at different times used as a political prison and location for torture and execution.

.

.

.

Lights in front of the well in the courtyard.

The Spanish Civil War lasted from 1933 to 1939. Another uprising led to the proclamation of the Catalan State in 1934 and the Committee of Antifascist Militias took over the castle in 1936. During this period, 1500 prisoners were held in the castle and 250 executed. Franco took over in 1939 and it continued in use as a military prison until 1960.

In 2007, the castle was returned to Barcelona Council as a municipal amenity, bringing a peaceful end to a long and often savage history.

.

.

.

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (National Art Museum of Catalonia).

Though it looks older, the National Palau of Montjuïc, known as Palau Nacional was constructed between 1926 and 1929 to be the main building of the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition.

.

.

.

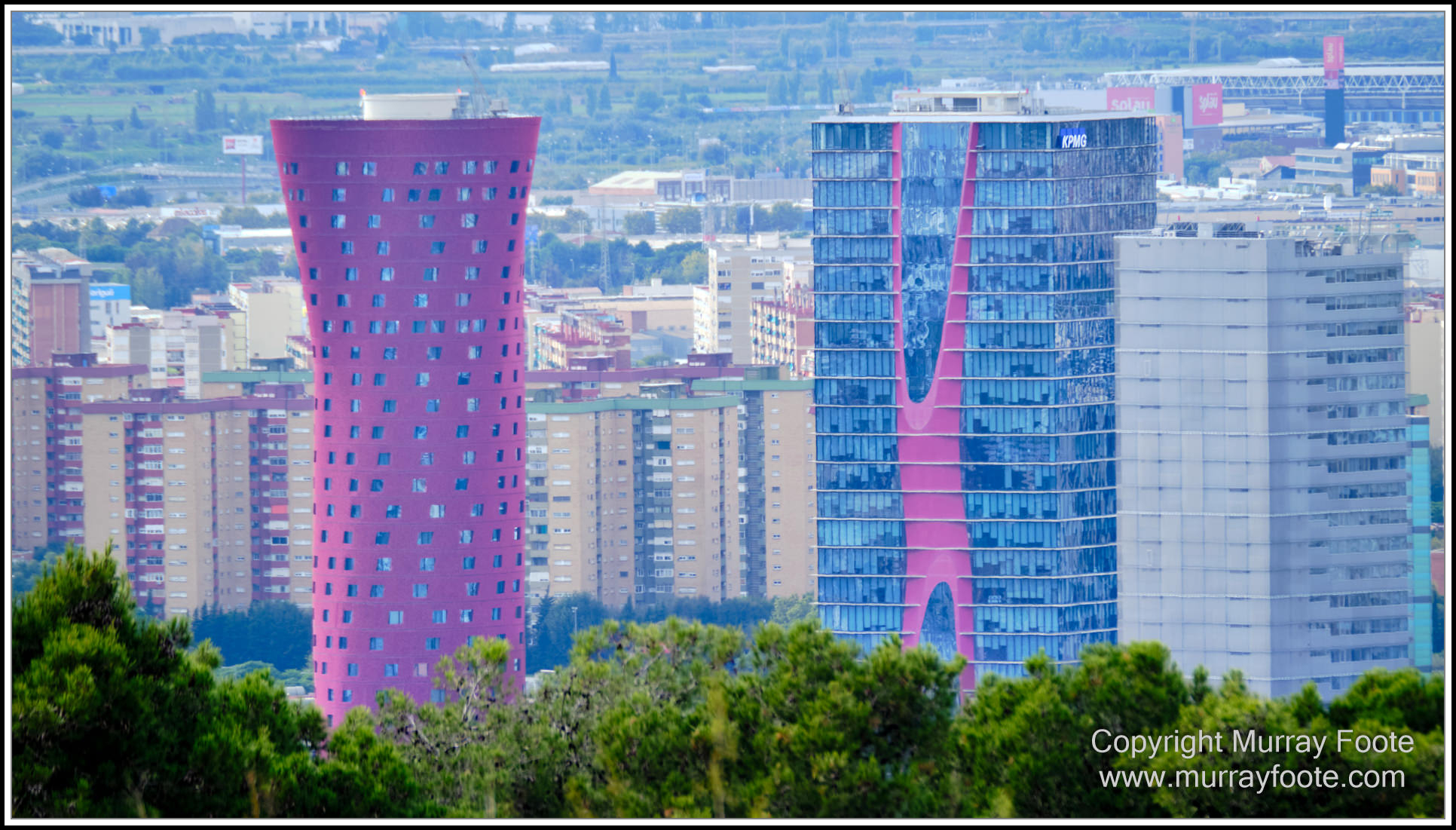

Hotel Porta Fira on the left; KPMG Building on the right.

.

.

.

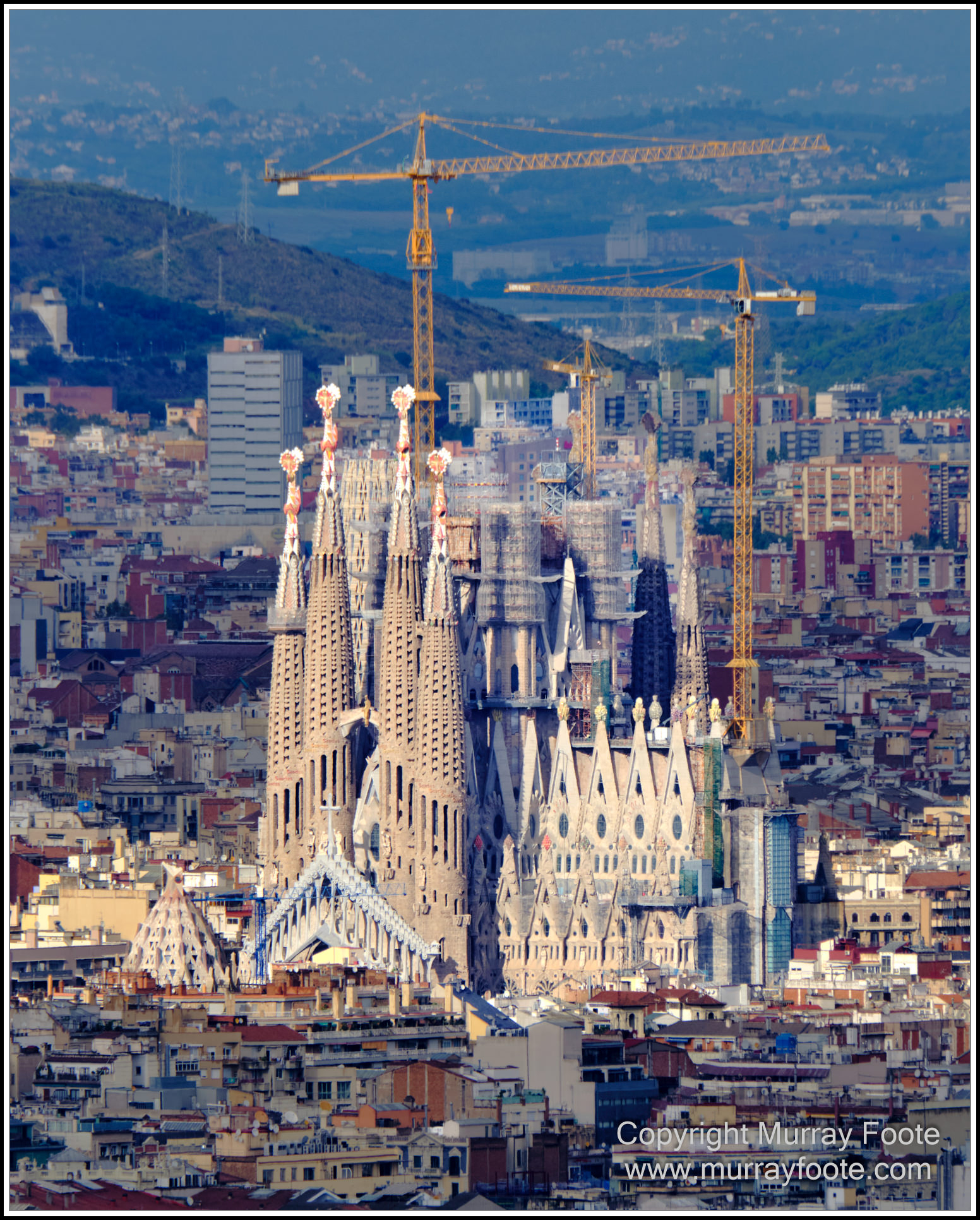

Sagrada Familia, familiar to many.

.

.

.

In the far distance: Tibidabo Amusement Park, Temple of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Torre de las Aguas de Dos Ríos (historic water tower).

.

.

.

This is where the poor people live. All they can afford is little coracles like these.

.

.

Granada Cathedral.

.

.

.

A small lighthouse at the port and a corner of the castle.

.

.

.

Sentries on duty.

.

.

.

And so we returned to Barcelona.

The teleportation process here is interesting, if much slower than you might see in the Star Trek documentaries on television. You climb into the teleportation booth and an AI display shows you continuously varying views of Barcelona, potentially with changing weather conditions. Then after a while you get out, and depending on where you were to begin with, you are either at the Castel or down in Barcelona. I understand there can also be a special feature where the AI display does not change and when you get out, you are exactly where you started from. There is also the possibility that as you walk around Barcelona, the entire experience is generated by AI. The wonders of modern technology.

And if you’re lucky, while you’re down in Barcelona, you won’t get shelled from the Castel de Montjuic.

.

.

.

.

Great overview. We love Barcelona

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much to see there. We really only scratched the surface.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have been to Arnhem Land and see some great Indigenous rock art.

I have discovered lost boomerangs in the deserts of West Australia.

I’ve seen Aboriginal fish traps in rivers that are still working today.

No great architectural feats to show after 60,000 years of freedom here yet look at what has been produced in Europe in the last 1,000 years.

Amazing developments in contrasting civilizations.

Not a criticism – just an observation.

LikeLike

True enough. I’ve seen some great rock art in North Queensland too.

LikeLike