Near Cordoba, Andalusia, Spain. 24th October 2018.

(Recent Posts, Top Posts, Subscribe and Search at bottom of page. Clicking image doubles size. Trip summary and links to posts.)

.

Monastery of San Jerónimo de Valparaíso.

We are heading to Medina Azahara and somewhat behind it on the hill is this monastery. It was built in the early fifteenth century but these days is privately owned and opened to the public only two weeks a a year. In a way we are looking at Medina Azahara though, because the monastery is said to have been built using materials plundered from there.

.

.

.

An ornate column at Medina Azahara.

.

.

.

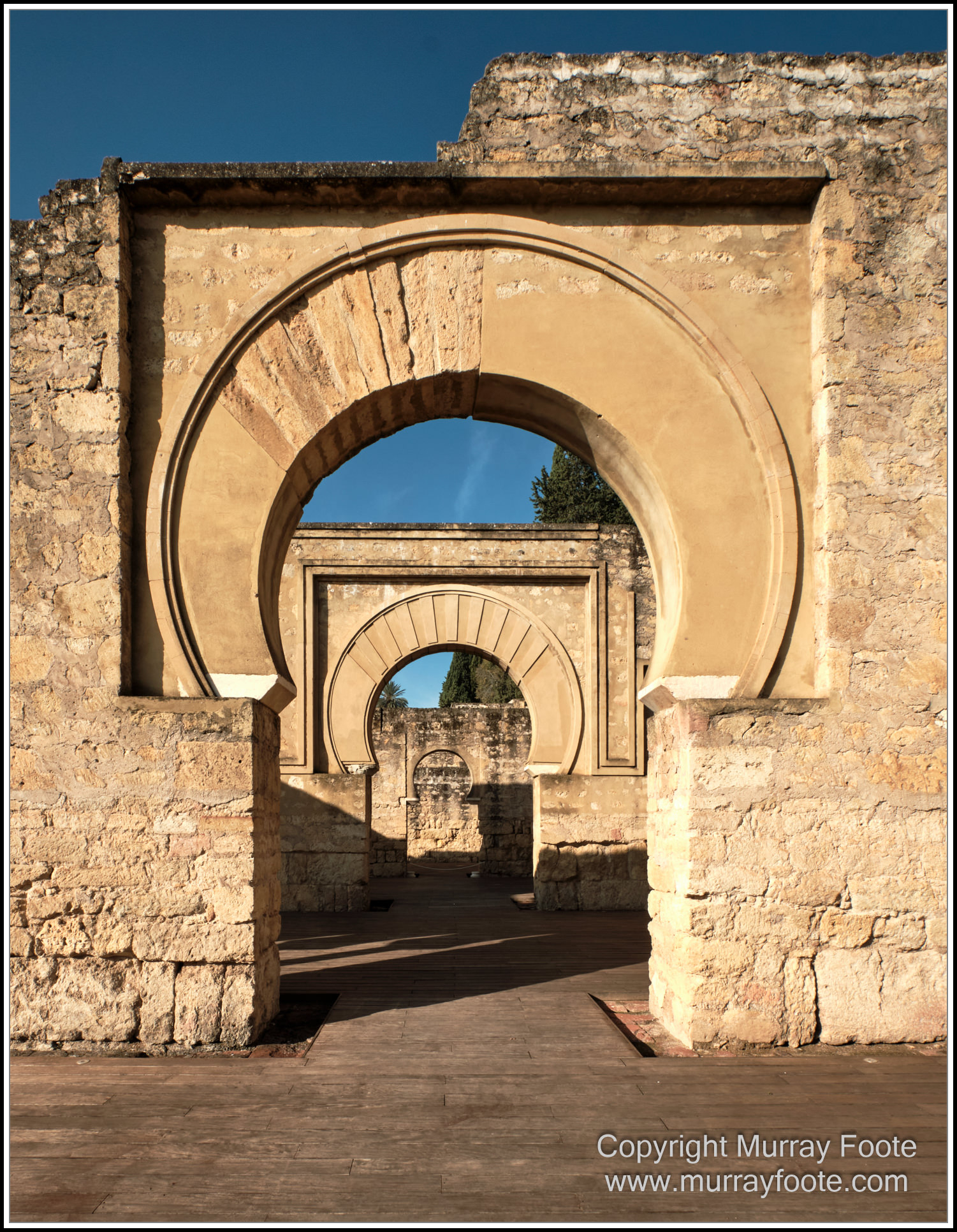

Upper Basilical Hall or Dar al-Jund, partly reconstructed, housed the main State administrative offices.

.

.

.

Same view, different angle.

Let’s put this in context with the early history of Al Andulus, or Moslem Iberia. The first great Moslem empire was the Umayyad Caliphate, based in Damascus. It invaded Iberia in 711, gradually conquered it and then set off to conquer France until conclusively defeated by Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732. Cordoba was capital city of Al Andalus as early as 717.

However, in 750, the Umayyads were overthrown in Damascus by the Abbasids (and who were later overthrown by the Fatmids). One grandson of the Caliph narrowly escaped and largely by himself journeyed first to the Euphrates and then through Palestine, Egypt and North Africa to Al Andalus where he gathered an army and in 755 defeated the Governor of Al Andalus and became Emir of Cordoba as Abd ar-Rahman I. He maintained power over Al Andalus and as well as defeating frequent rebellions, he also defeated armies sent by Charlemagne and the Abbasid Caliphate.

His descendant Abd ar-Rahman III became Emir of Cordoba in 912 at a time when Cordoba’s power barely extended beyond the city walls. He slowly reestablished control over Al Andalus and declared himself Caliph in 919, also creating a period of cultural flowering and tolerance.

His mother was a Christian captive, probably from the Pyrenees, and his paternal grandmother was a Christian princess from the Kingdom of Pamplona, later Navarre, from both sides of the Western Pyrenees. So he was of Arab and Hispano-Basque extraction. He had fair skin and auburn hair which he is said to have dyed black to appear more Arab.

From 936 to 940, he built Medina Azahara (or Madinat al-Zahra), the remains of which we see now. This was a fortified palace and city five kilometres to the west of Córdoba. It became the capital of the Caliphate of Córdoba and its centre of government, moving from Córdoba itself.

After the death of his son, Al-Hakam II (r. 961–976), the city ceased to act as the center of government as a usurper took over in a different location. It would have been during this period that Gerbert of Aurillac, the future Pope Sylvester II, studied at Catalonia, Seville and Cordoba. A scientist Pope, and unfortunately not a typical Pope, he introduced many elements of Arab learning to Christendom including decimal numbers.

Abd ar-Rahman I had Berber troops from North Africa as a significant proportion of his forces because they did not have local allegiances. I presume they retained a significant military influence. Between 1010 and 1013 Córdoba was besieged by Berber factions, and Medina Azahara was left pillaged and in ruins, with many of its materials subsequently re-used elsewhere. It became buried and was not relocated until the 19th century, with excavations beginning in 1911.

After a period of civil war and contention, the Caliphate of Cordoba disintegrated in 1031. The last Moorish holdout was the Kingdom of Granada, that fell in 1491. We shall see Granada and the Alhambra in due course.

.

.

.

Upper Basilica Building. There are also three smaller arch-doorways on each side.

.

.

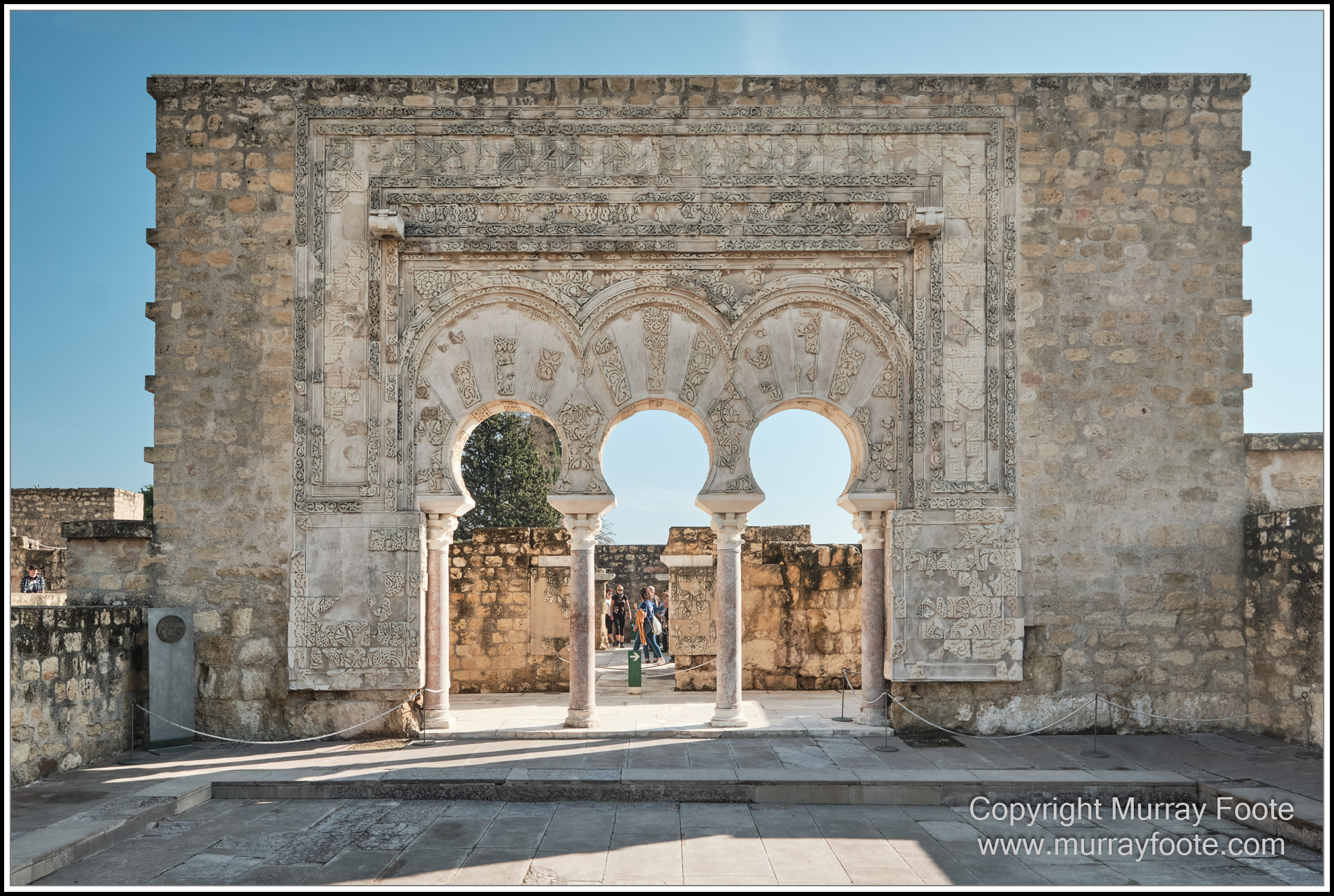

Bab al-Sudda, the ceremonial entrance to the Alcazar. Colours are faded but you can see some similarities to the Mezquita of Cordoba.

.

.

.

A detail of the top of the second-left arch.

.

.

.

Remains of the mosque.

.

.

.

The stables.

.

.

.

A street, perhaps.

.

.

.

The Upper Garden in front of the Salón Rico.

The current trees and shrubs were planted in modern times, presumably using the planting patterns indicated by the surviving layout. The city received water from an aqueduct.

.

.

.

One of the two reconstructed porticos at a side of the central courtyard of the House of the Water Basin.

.

.

.

Reconstructed portico in the main courtyard of the House of Ja’far.

.

.

.

Side view of same portico.

.

.

.

.

Thanks for introducing me to a new place.

LikeLiked by 1 person