Near Malaga, Andalusia, Spain. 25th October 2018.

(Recent Posts, Top Posts, Subscribe and Search at bottom of page. Clicking image doubles size. Trip summary and links to posts.)

.

The Sleeping Giant, in shadow from the clouds.

We are in Antequera, visiting two dolmens, which are megalithic structures constructed with standing stones.

.

.

.

Entrance to the Viera Dolmen.

You can see some of the monoliths lining the sides of the entrance. Upper stone work is modern, to prevent subsidence. The dolmen is a long corridor, 21 metres in length and 1.8 metres high, that slightly widens from 1.3 metres to 1.6 metres when it meets the main chamber. The main chamber is 2 meteres high and 1.8 metres wide.

.

.

.

Small end chamber.

This is a small chamber in the back wall of the main chamber.

.

.

.

Looking out of the Viera Dolmen.

This gives you a better idea of the monumental nature of the construction. The walls are massive stones one-third buried in the earth, and the ceiling consists of equally massive capstones. There is no mortar and they fit together with extraordinary precision.

.

.

.

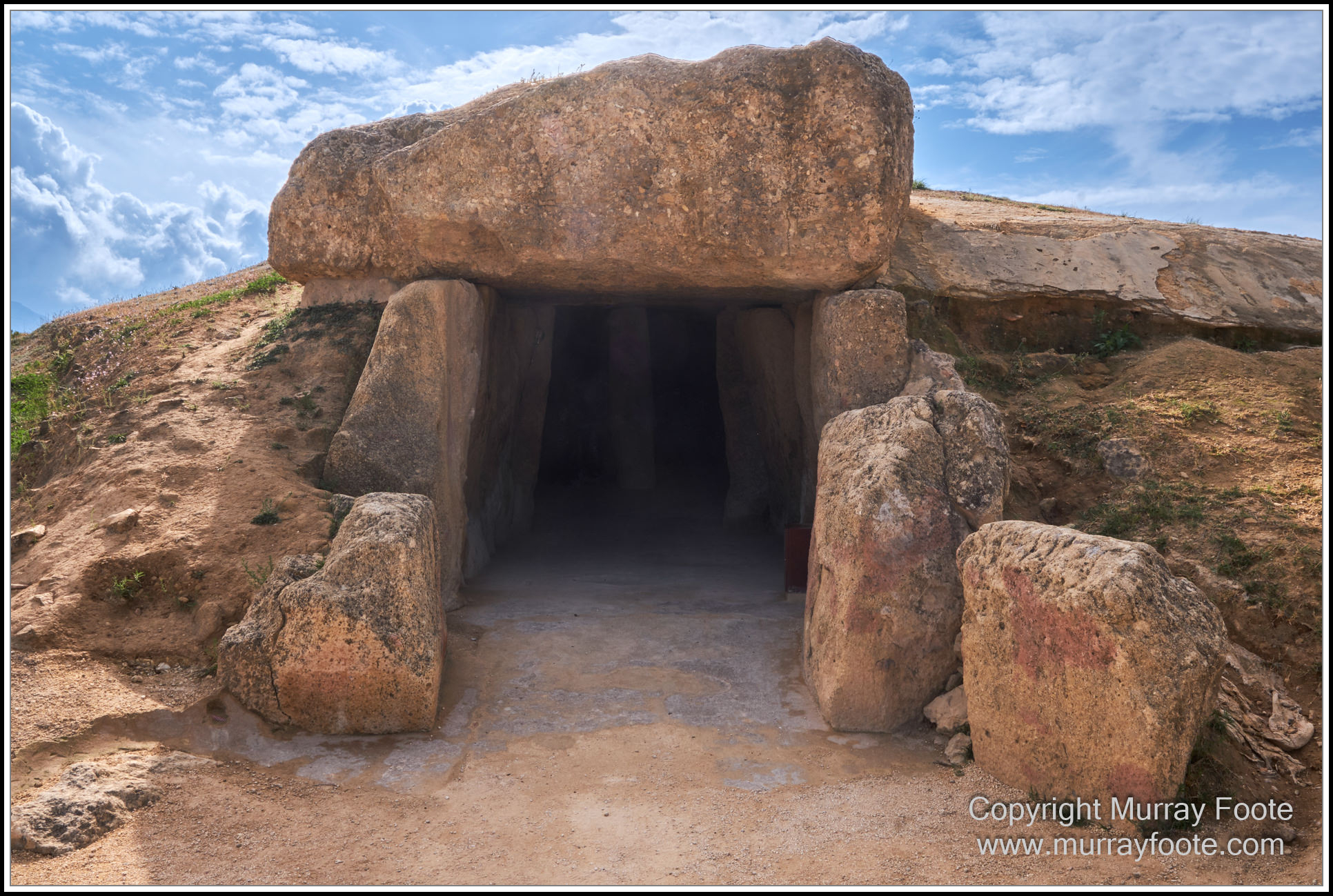

Entrance to the Menga Dolmen.

The nearby Menga Dolmen is larger, 25 metres long, width up to 5.7 metres and ceiling height 2.5 metres at the entrance rising to 3.45 metres at the rear. It is a littler older than the Viera Dolmen at 6,000 years old. That is a thousand years older than Stonehenge or the first pyramid. It is probably also older than Keith Richard.

That capstone you see weighs 150 tonnes and the 32 stones that form Menga weigh 1,140 tonnes. This is said to be equivalent to two 747 jets loaded with passengers, though I have not tried to lift one to verify this. The obvious explanation for the construction method is that Obelix is not a myth and it was built by a single person twirling stones above his head. Sometimes the most obvious explanations do not withstand careful analysis though.

.

.

.

Well, well, well.

There is a well at the end of the dolmen, covered by a protective grille to prevent children hurling themselves or their parents in. I have not found any descriptions of this so can’t describe its original purpose.

Wikipedia claims that when the dolmen was opened in the early nineteenth century, there were several hundred skeletons inside. All other sources seem to claim nothing was found in it.

.

.

.

Interior view.

The stones were quarried about 850 metres away, at a location 50 metres higher. They were slid down the slope on sleds on a road and eased into place using ropes, pulleys and counterweights. No later adjustment was possible. Not merely the logistics, but the level of technical achievement was remarkable. There appears to have been no earlier process of trial and error on smaller monuments.

.

.

.

Looking out towards the Sleeping Giant.

The orientation was no accident. The sun rises over the Giant and into the Dolmen at the time of the summer solstice.

.

.

.

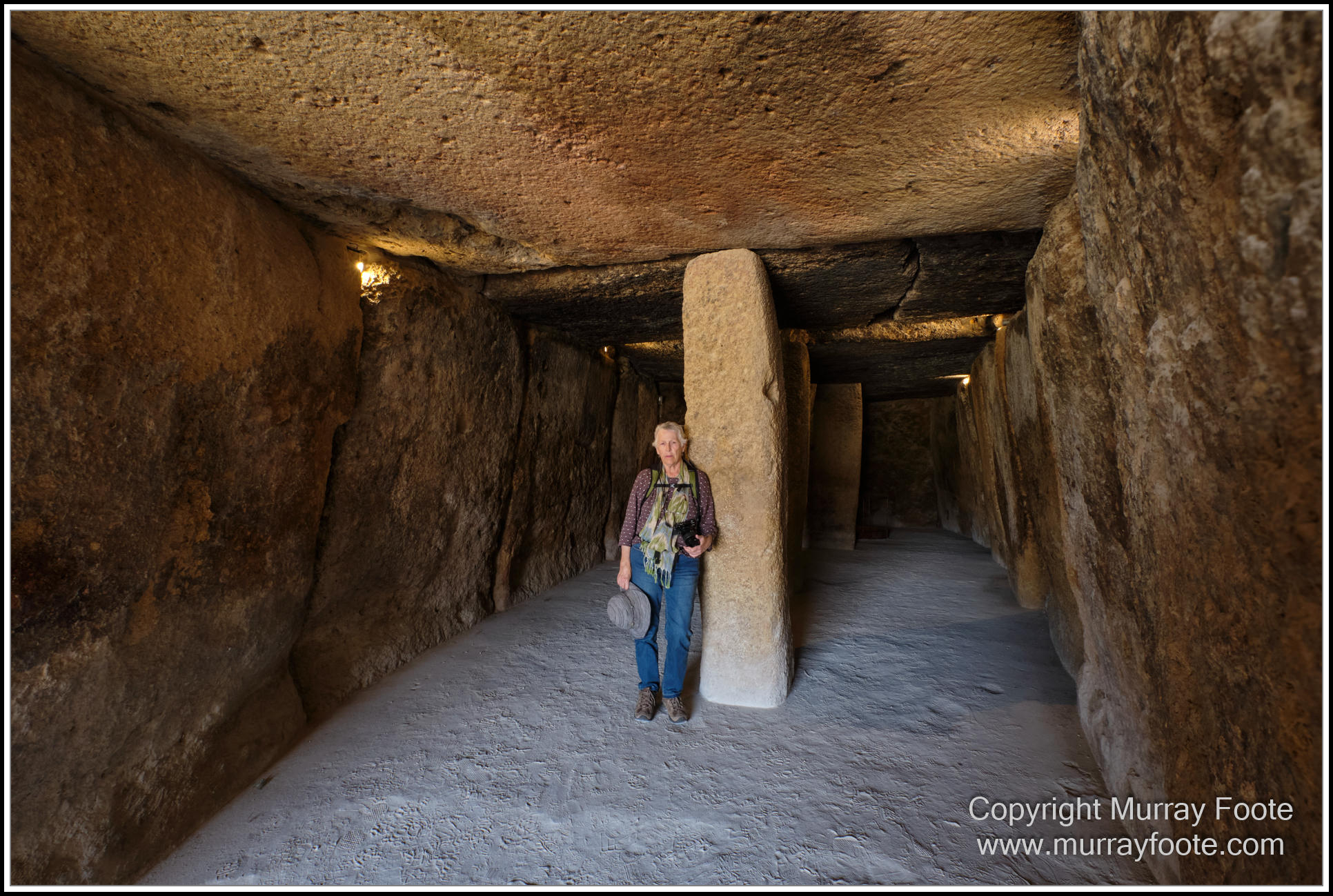

Interior view.

I asked Jools to stand by the pillar for a better sense of scale. The well is behind the far pillar.

.

.

.

The Sleeping Giant, now in full sun.

The Sleeping Giant is more commonly called Peña de los Enamorados, or Lovers’ Rock, from a legend that two Moorish lovers from rival clans threw themselves from the rock when pursued by her father and his men. Until relatively recently though, the dolmens were just huge huge mounds of earth, unknown to be archæological sites, and the rock no doubt looks quite different from different angles. This is the view from the Dolmen of Menga though, which was built specifically to align with that view. The more recent name therefore trivialises ancient significance due to historical ignorance.

A small tomb and cave, the Abrigo de Matacabras, is on the north-west slopes of the Giant, so on the chest or neck. It is associated with the Dolmen of Menga, is about the same age (around 6,000 years old) and contains schematic cave paintings. It is probably not open to the public.

A small tomb, the Piedras Blancas tomb, was also discovered in 2023 on the chest of the Sleeping Giant. It is about 5,000 years old.

There is another megalithic site nearby we could have visited had I read one of the information signs, and not just photographed it for later reference. This is the Tholos of El Romeral, nearly four thousand years old and about the same size as Menga but made using much smaller stones. It is described as a false cupola tomb. “A false cupola tomb, also known as a Tholos, is a burial structure characterized by a rounded dome or corbel created by placing progressively smaller stones or bricks on top. This architectural style is a hallmark of prehistoric Spain, particularly during the Neolithic and Bronze Age, and is used for funerary purposes. The design involves constructing the tomb in concentric circles, showcasing a high level of architectural detail and complexity.”

.

.

.

Alcazaba of Antequera, from a viewpoint on a city road.

The Sleeping Giant is in the far distance and in the middle distance is the Alcazaba of Antequera and part of remaining city walls. It is a Moorish castle erected in the 14th century over Roman ruins, to try to keep out the Christian invaders. The city held out against attacks for nearly 200 years but was conquered by a Castillian army in 1410 and most of the inhabitants expelled.

Antequera was called Anticaria or Antiquaria by the Romans. The area was Carthaginian from around 230BC to 200BC when the Romans took over. The Vandals conquered around 410AD and after they moved to North Africa it became part of the Visigothic Kingdom, effectively converted Christians trying to be Romans. Anticaria was conquered by the Moslems in 716.

.

.

.

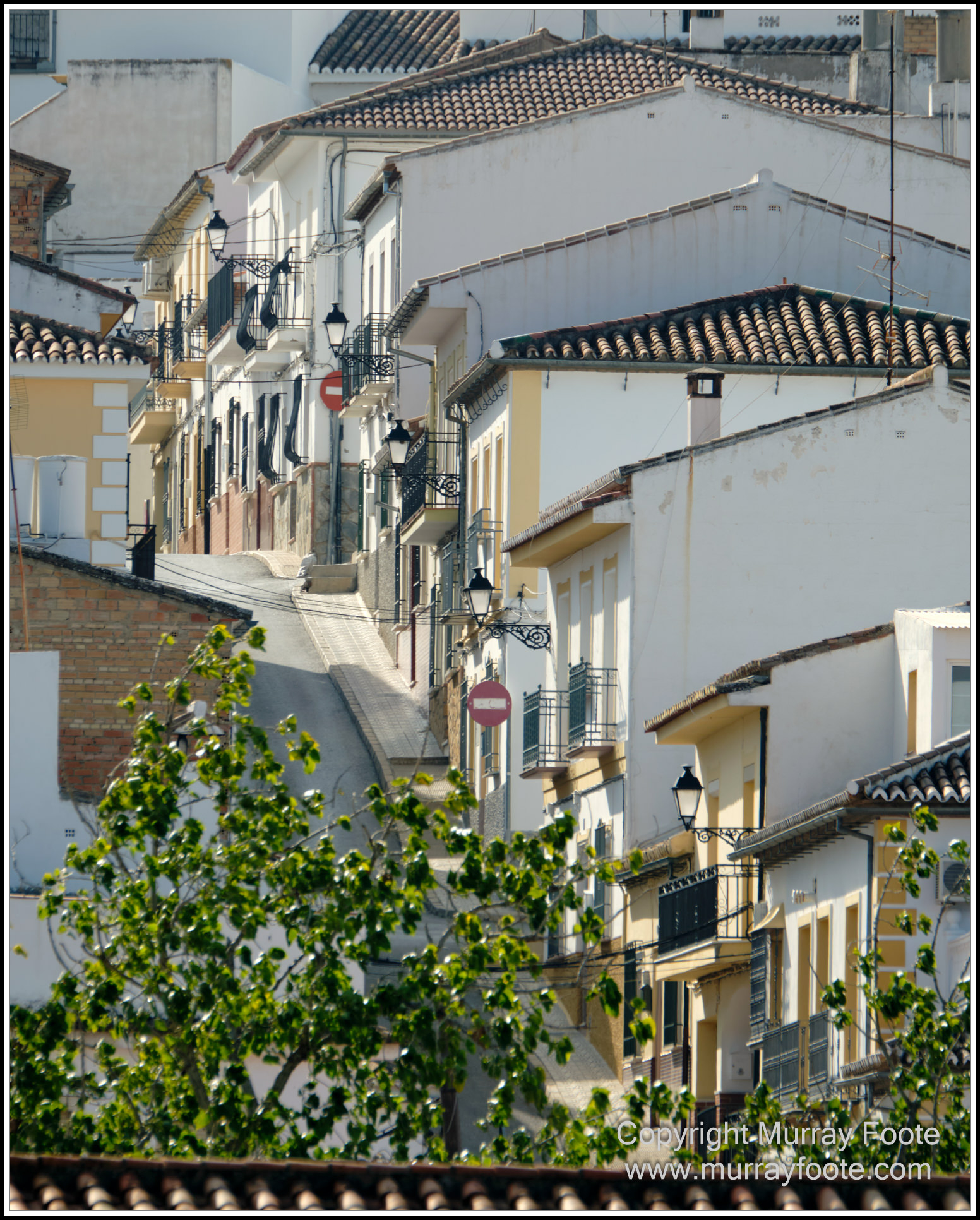

As we leave Antequera, here is a long telephoto shot of a city street. Evidently it is a one-way street, downhill only. Working brakes would be desirable. Skateboards would be exiting, for a short period at least.

.

.

.

.